Nearly 11,000 convicts sent to Van Diemen’s Land were Irish and approximately 4000 were Irish women. Margaret Bradburn was a quiet Irish lass from County Cavan. It was 1852 and the Great Famine had created mass starvation and disease in Ireland.

She stood in the docks listening to the sentence in shock. Seven years transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, this was her second offence, as she had been caught a month earlier stealing a cloak from Catherine Reilly at Ballyhaise, in the Parish of Castleterra. This time she had been charged with burglary for stealing clothes – coat, petticoat & shawl. Would this turn out to be a blessing or a curse, this journey to the ends of the earth. Only time would tell.

Margaret embarked on the vessel ‘Midlothian’ on 2 November 1852 at Kingstown Harbour, five miles from Dublin. The surgeon’s journal entry reads:

“Having arrived at Kingstown, Ireland on the 16th of October 1852 and embarked on the 30th of October and the 2nd of November, two matrons, two intermediate passengers, twelve free settlers, 170 convicts and 19 children of convicts, which with myself made 206, but the mean ratio for the whole period was only 204 4/41 out of which number one hundred and three were between the ages of 15 and 25 years. Fifty between the ages of 25 and 35 years. Twenty five between the ages of 35 and 45 years. One between 45 and 55. And twenty seven under the age of 15 years”.

The ‘Midlothian’ set sail on 17 November for Van Diemen’s Land. The voyage (BV0746) would take 99 days with two deaths reported. Lucy Gorman died on board from Pneumonia. The health of the convicts was David Thomas’s main concern as the ship surgeon. He made sure all convicts and every person on the Books for Rations had limes and potatoes three times a day. The potatoes being a favourite with the Irish female convicts. Illnesses during the ‘Midlothian’ voyage included: 1 case of synochus (fever), 5 cases of phlogosis (inflammation), 2 cases of bronchitis and 2 cases of pneumonia which proved fatal for both convicts. This had to be considered a successful voyage when compared to the ‘Hillsborough’ voyage in 1798-1799 (The vessel that Robert Jillett, Thomas Bradshaw and Elizabeth Bradshaw arrived on fifty-four years earlier), which recorded 95 deaths from yellow fever and dysentery.

Governor Hunter wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Colonies:

“The Hillsborough has just arrived with a cargo of the most miserable and wretched convicts I ever beheld. Were you, my dear Sir, in the situation in which I stand, I am convinced all the feelings of humanity, every sensation which can occasion a pang for the distresses of a fellow creature, would be seen to operate in you with full force.”

The ‘Midlothian’ arrived at Hobart Town in Van Diemen’s Land on 24 February 1853. Transportation of female convicts to Van Diemen’s Land would soon end after sixty-five years. The arriving convicts were documented by the Board of Health and full description lists complied. Margaret’s description on arrival reads: height 4’10”, complexion ruddy, head medium, eyes grey, hair light brown, visage oval, eyebrows brown, noise large, mouth medium, remarks section listed 3 dots on noise. It was unusual for Irish female convicts to have tattoos, it is unclear if the three dots are tattoos or moles. Margaret was a protestant and could not read or write, which was common for female convicts from Ireland.

On 3 March Margaret was sent to the Cascade Female Factory to await assignment. The Cascade Female Factory was two miles from town. It was locally call The Factory and also referred to as “the valley of the shadow of death”.

She was hired by Mr Horace Nelson Rowcroft Esq of New Town on 9 March 1853. Margaret was returned to the Cascade Female Factory on 29 August 1853 for being absent without leave and she received six months hard labour and additional six months probation. The magistrate was Algernon Burdett Jones at Glenorchy. The hard labour was most likely at the washtubs at the female factory. On 27 July 1854 Margaret was rehired by Mr Horace Nelson Rowcroft to complete her additional six months probation. Some time in late October or November 1854, Margaret became pregnant and because of this and that she was still in servitude, she entered the Cascade Female Factory for the birth of her baby girl (15 Jul 1855 Frances Jane Cripps). The baby was baptized on 5 August 1855 at Davey St Congregational Church and the father listed as William Cripps. William Cripps was not the father as DNA proves in 2018, and it confirmed 99% Horace Alexander Rowcroft Jnr (son of Horace Nelson Rowcroft) was most likely the father of Margaret’s daughter. Frances was christened Frances Jane (Cripps) as the mother of William Cripps (the “named father” on registration) was also Frances Jane (Gregory). So perhaps Margaret and William fully believed William was the father.

Margaret was granted a Ticket of Leave on 16 January 1855 and permission to marry John Boulter on 8 April 1856. The marriage took place on 29 April 1856.

Margaret was Free by Servitude on 3 April 1859. Margaret had served six years of her seven year sentence. Margaret and John had at least ten children including twin girls. This seems to be an exception to the rule, as only a small majority of male and female convicts ever married or had children even though nearly ninety percent of transported women were of childbearing age.

When we look at Margaret’s offence and sentence in context with other Irish female convicts she presents as being typical for the time. 83% Irish female convicts received seven-year sentences and 60% committed the offence of burglary.

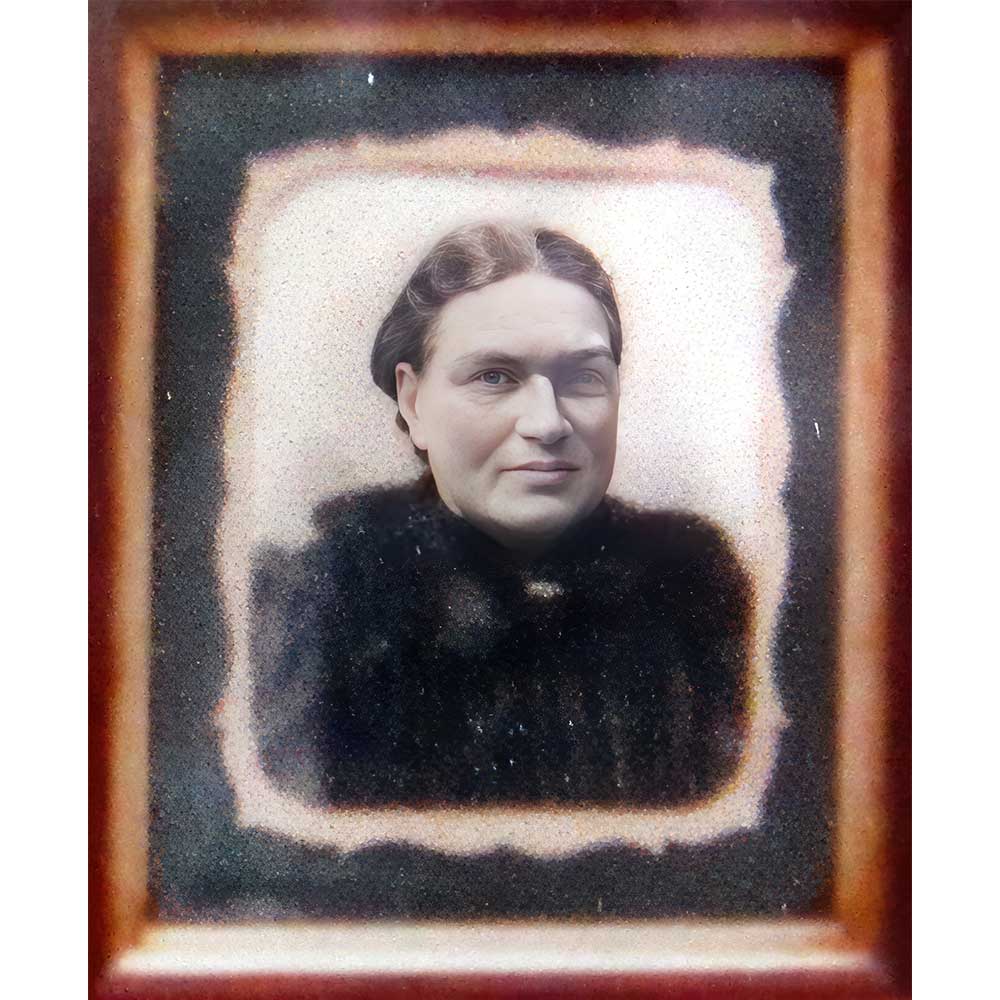

Margaret died on 25 December 1910 at Molesworth of heart disease and was buried at the North Circle Cemetery, New Norfolk. The death notice in The Mercury newspaper referred to her as a ”relic of the late John Boulter”. No doubt if Margaret had reflected on her past fifty-eight years in Tasmania, she would have realised that her life would have been very different, had she stayed in Ireland. Being transported to Van Diemen’s Land was indeed, a blessing in disguise for her and the future generations of her bloodline. Margaret survived her ordeal as a convict and had gone on to be a productive member of the new society in Van Diemen’s Land. Margaret (Bradburn) Boulter was my second great grandmother.

Written by Ann Williams-Fitzgerald 2019